New Search Filter Brings Large Geography Support to Lifestyle Reports

Product

| 10 Mar 2026

In January 2017, New York City made good on a big promise to add a major new transit line to its subway network. Phase 1 of the Second Avenue Subway Construction Project launched to great fanfare, reshaping transit accessibility and transportation patterns on the Upper East Side and other neighborhoods. The new line has attracted over 200,000 daily riders and meaningfully reduced both commute times to downtown and rider congestion on nearby transit services.

Yet, if impacts have been huge, so too has the wait. The subway line was initially proposed in 1919! Construction started in 1972 but was halted for financial reasons several years later, only to be renewed in 2009, after which it took a decade to complete. The project’s next phase won’t be completed until 2029, while future steps remain little more than exercises in future-gazing. Most large-scale infrastructure projects don’t take an entire century to develop, but there’s no denying that they are long in the making and few and far between.

Why do governments spend so much money and time on such projects? And why do communities push for them? Clearly, because this kind of infrastructure can transform a city’s transportation patterns. Since the project’s completion, the impacts make clear that this is no mirage. And in a day and age when cities are choking on greenhouse gas emissions, congestion, and the cost of road upkeep, the promise of large projects aimed at making transportation patterns more sustainable shines brighter than ever.

Yet focusing so much attention on large-scale, complex projects risks blinding us to the even larger impacts of something hiding in the shadows.

In the run of a year, millions of smaller yet still meaningful decisions are made about where and what to build and where to relocate. In every case, these decisions influence how people will move to, from, and around the site in question.

For example, everyday, real estate developers make decisions about where to build new housing developments or office towers. Those decisions influence how future occupants are likely to commute to and from those sites, move around for daily errands, get kids to school, and so on. An office building located far from transit and amenities but near large highway exchanges and with a large parking lot will almost certainly mean cars will be the dominant mode of commuting and that occupants will find it hard to use their office as a hub for non-work needs, like daycare, grocery shopping, pharmacy visits, and so on. By contrast, a new multi-family housing development located near a transit hub and with easy access to shops, restaurants, schools, and parks will almost certainly imply fewer car trips and instead more walking, biking, and transit trips.

Real estate developers are one key actor making many of the decisions in the long tail, but they certainly aren’t the only ones. Every day, households make decisions about which neighborhood to move into, financial institutions make decisions about which type of real estate project to underwrite and which to deny, employers make decisions about where to locate offices, and merchants make decisions about where to locate new stores. In every case, mobility hangs in the balance as residents, tenants, employees, and shoppers move to, from, and around the bits and pieces of the built environment that appear so small in the shadow of large-scale infrastructure but that collectively dominate the landscape.

Source: Unsplash

Source: UnsplashExamples abound. Suburban developments tend to offer spacious private homes with large gardens but no grocery stores, schools, or transit stations within walking or biking distance. Large-scale retail locations are often built in places that make access difficult in anything other than a car. Employer decisions about office site selection often ignore or downplay the importance of transportation emissions, leading to decisions that privilege cars over alternative modes of travel for commuting and that neglect the importance of nearby amenities that would allow employees to run household errands from the office hub, displacing trips that might otherwise be done by car.

One response to all this is to suggest that the electrification of personal vehicles will make this debate moot by removing emissions without requiring travelers to give up their cars. To be sure, electric vehicle sales are picking up — analysis by Experian showed that, in the first half of 2021, the number of new electric vehicle (EV) registrations in the United States was 117.4% higher than in the same period one year prior. Yet, this still represents a micro-fraction of overall vehicles on the road. By mid-2021, EVs were still only 2.4% of all new light-duty vehicle registrations. Some predict that EVs will account for up to one-quarter of new sales by 2035, yet by then they will still only account for 13% of the cars on the road because households tend to hold onto older cars for a decade or two. Even by 2050, when EVs are predicted to make up 60% of new vehicle registrations, most personal vehicles will still be gas-powered owing to the slow pace of overall fleet turnover.

For now, EVs also aren’t as clean as they sound. Manufacturing the batteries that EVs rely on remains a carbon-intensive process while running vehicles on electricity continues to be carbon-intensive in places where electricity is generated by burning fossil fuels, as is the case in many places in the United States today. Big gains will come as electricity grids move away toward cleaner energy sources, but we aren’t there yet. And it’s worth underlining that even the cleanest EVs do nothing to address congestion, hunger for parking and road infrastructure, and traffic deaths, all of which are important factors in the livability of cities. In the long run, the electrification of personal vehicles will help clean the air of emissions, but it won’t solve the larger problems associated with car-oriented city design.

The sheer quantity of these decisions is mind-boggling. For example, in 2020, the United States Postal Service received nearly 36 million change of address requests. In 2019, in New York City alone, close to 8,000 permits were handed out for new building construction, while 175,000 newly built dwelling units were released onto the market. All of that adds up to an awful lot of site selection and relocation decisions.

Part of what makes large-scale infrastructure projects so complex is the attention put into projected impacts on transportation and social life. By contrast, very few of the millions of decisions in the long tail ever get such focused attention. Transportation impacts — important as they are for carbon emissions, congestion, livability, and other things we care deeply about — are often ignored, under-weighted, or miscalculated in everyday decisions made by developers, investors, and homebuyers.

If predicting mobility patterns and engineering outcomes is hard for large-scale infrastructure projects with decades of time at hand, it is even harder for actors making much smaller and faster decisions given their limited access to data and on-the-ground research. The end result is that everyday real estate decisions tend to reinforce our already car-dependent, emissions-heavy, congestion-affected city systems.

It’s hardly novel to point to the car domination of our cities as problematic. Most people have heard of Jane Jacobs’ approach to urban design, which privileged higher density, mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods. The school of New Urbanism has long advocated a similar human-scaled approach to urban design, centered on walkable blocks, housing and shopping in close proximity, and accessible public spaces. Transit-oriented development (TOD) is an approach to urban design that combines dense and mixed-use neighborhoods where most needs can be met on foot or by bike, on the one hand, with connections to the rest of the city by high-quality transit service, on the other hand. The ‘15-minute city’ is the latest version of this approach to urban design, prioritizing the same kind of dense, mixed-use, walkable, and cyclable neighborhoods where “most human needs and many desires are located within a travel distance of 15 minutes.”

Calls for this kind of more sustainable, less car-dependent mode of urban development have grown in number and volume in recent years. Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, famously centered her successful 2020 re-election campaign on the 15-minute city concept. Shaun Donavon, the former United States Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, launched his recent bid to become New York City’s mayor with a promise to support the creation of 15-minute neighborhoods, where residents lived within a short distance of rapid transit, a place to buy fresh food, a good school, and a park. Chicago recently created an Equitable Transit-Oriented Development Pilot Program to encourage high-density, low-parking developments near rapid or high-frequency transit.

The focus on transportation — in particular, the role of cars for personal transportation — is hardly surprising given its impact on the environment and the livability of cities. In 2019, transportation accounted for 29% of overall greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, making it the largest contributor of emissions in the country. And within that category, 58% of emissions came from light-duty vehicles, the bulk of which is used by households for commuting, shopping, school-going, park-visiting, and so on.

The uptake of these concepts among municipal decision-makers is promising, to be sure. Implementing regulatory reform or city-wide programs to privilege 15-minute city or transit-oriented urban designs will need to be an important part of any overall drive towards more sustainable cities. Yet, putting all our hope in regulation and policy is no different than waiting for large-scale infrastructure projects to reshape transportation patterns in a sustainable direction. These kinds of projects and reforms take years, sometimes decades (at times even a full century!), to be implemented.

Meanwhile, the steady hum of everyday land-use decisions continues, collectively shaping and entrenching transportation patterns that put the car at the center of how our cities operate. If we want our cities to become more sustainable, we have no choice but to grab hold of the long tail and make it work in favor of sustainability and livability.

The good news is that there is already a notable turn towards sustainability among real estate investors, developers, and homebuyers. On the investor side, Ivanhoe Cambridge and Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, which together hold over $90 billion in real estate assets, have each committed to implementing aggressive net-zero policies across their portfolios in the coming decades. Many others are following suit.

Large-scale property managers aren’t far behind. Companies like Oxford Properties, which manages some $70 billion in real estate assets around the world, now regularly report on the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) impacts of their activities, outlining on an annual basis how they have improved and what they commit to doing in the future to improve even further.

Builders have shown a sizable and rapidly increasing interest in sustainable building practices in recent years. The U.S. Green Building Council reported that green, LEED-certified homes grew 19% between 2017 and 2019 to reach an all-time high with close to 500,000 single-family, multi-family, and affordable housing LEED-certified units around the world, more than 400,000 of which were located in the United States. A separate report showed that increasing numbers of real estate developers are taking on green projects, and a rising number are becoming fully dedicated green builders. For example, in the United States, the percentage of single-family home builders focused almost entirely on green projects was 19% in 2017 and is expected to hit 31% by 2022. Among multi-family developers, the percentage doing more than 60% of their projects green rose from 23% in 2014 to 36% in 2017 and is expected to be 47% by 2022. Even more encouraging, multi-family developers doing more than 90% of their projects green is expected to grow from 29% in 2017 to 40% in 2022.

All of this is very good news for cities and the climate, yet it suffers from a major lacuna. The transportation patterns of building occupants — residents, employees, shoppers, and others — are virtually ignored in this major shift to sustainability among real estate actors. And this is particularly problematic because transportation-related impacts — in particular, greenhouse gas emissions — outweigh those coming from in-building energy systems, yet the latter get far more attention.

Take Ivanhoe Cambridge’s recently released pathway to achieving net zero carbon by 2040. The company is pushing the envelope when it comes to implementing sustainability in its real estate investment decisions. Yet, even for the best in class like Ivanhoé Cambridge, the question of transportation is obviously absent.

Ivanhoe’s pathway to net-zero commits to a host of initiatives to draw down the carbon footprint of its portfolio, including dramatic improvements in the energy efficiency of buildings, expanding property reliance on renewable energy sources, improving the use of more sustainable building materials, and more. Yet it does not document or commit to reducing the hulking downstream carbon footprint generated by resident and tenant transportation patterns.

Tricon Residential offers another example. Tricon owns approximately $8 billion in residential developments across the United States and Canada, and is particularly active in the rental market, including in single-family rentals. In its 2020 ESG Roadmap, Tricon reported on performance across a range of environmental and social factors, yet it virtually ignored how residents move to and from their homes in order to work, play, shop, get to school, and so on. Tricon’s report points to sustainable building materials and efficient energy systems but has little to say about how their building and operational practices make certain kinds of transportation choices more likely than others.

It might be easy to assume that transportation impacts are the responsibility of occupants, not investors or developers. Yet the reporting practices of Ivanhoe Cambridge, Tricon, and others in the sector already make clear that this isn’t the real issue, as they already dedicate tremendous attention and resources to improving the environmental impact of occupants in other ways. The most notable example is the already-accepted focus by real estate investors and developers on improving the efficiency of in-building energy systems, the emissions of which are ultimately driven by the daily decisions of occupants to use more or less electricity. Transportation emissions are similarly driven by the daily decisions of occupants and are similarly structured by the location and design choices of developers and investors. Yet, despite the similarity, the sector ignores its impact on transportation emissions. Ivanhoé Cambridge and Tricon are both leading voices on sustainability and ESG reporting in the real estate sector, yet the wider sector’s blind spot on transportation impacts is hampering their view of the full carbon footprint of their portfolios, leaving a key environmental risk hidden.

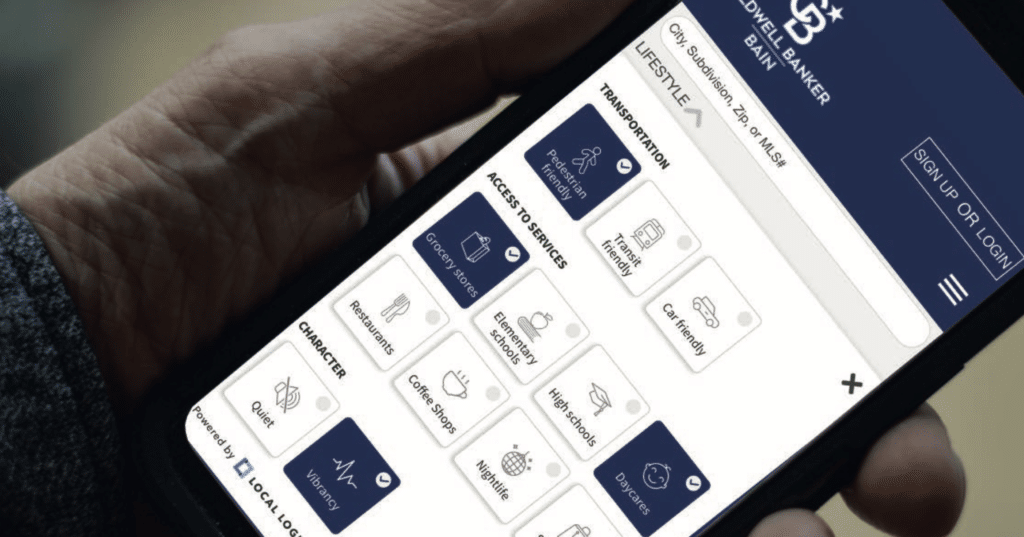

CB Bain leverages Local Logic’s data and insights to help its customer base make better real estate decisions

CB Bain leverages Local Logic’s data and insights to help its customer base make better real estate decisionsA big part of the problem is the information gap faced by developers, investors, and homebuyers today. When choosing a site to build on, a real estate developer often has no better access to data about what is nearby and what modes of transportation are likely to dominate than does anyone with access to Google Maps. Beyond eyeballing a map to identify nearby points of interest, there is no easy way to explore and summarize how well or poorly a site lives up to the standard of a sustainable neighborhood or ‘15-minute city’. One alternative for developers is to hire researchers or to engage a research consultancy to compare different sites when it comes to nearby transportation, shops, amenities, how walkable and vibrant the neighborhood is, and so on. But doing so is often too costly or slow. The end result is that, even for developers who search for ways to create sustainable neighborhood and transportation outcomes, it’s hard to know where and what to build.

Large-scale investors, asset managers, and property managers arguably face an even greater challenge. Holding properties across many neighborhoods, cities, and countries makes on-the-ground knowledge about environmental risks rooted in transportation patterns and neighborhood composition near impossible to monitor. At least, not without good data and technology focused on this problem specifically.

In the past, investors, asset managers, and property managers faced a similar challenge when it came to understanding the operational efficiency of in-building energy systems. Across hundreds of thousands of properties, how to know which properties had more or less sustainable energy use systems? But today that problem is starting to be solved by new building-level energy use data collection processes that roll up to portfolio-level scoring and ranking systems, such as those driven by GRESB. For the risks associated with transportation patterns and neighborhood composition, no similar system exists, leaving investors either struggling to piece together the data themselves or turning a blind eye to the risk altogether.

For homebuyers, the information challenge is no less present. Quality of life is a primary concern, while an increasing number of homebuyers also want to understand the environmental footprint of living in one location versus another. Many want a home that combines indoor comfort with access to high-quality shops, restaurants, amenities, public and green spaces, and schools. And they increasingly want those things close enough or accessible enough to make car travel unnecessary, or at least an exception not the rule. Demand for this kind of lifestyle is evident in both research findings and raw market data. A study by Redfin of over 1 million home sales between January 2014 and April 2016 across 14 major metro areas showed that a one-point increase in their transit score was correlated with an increase in the home price of over $2,000 and that the effect was even larger in cities where most neighborhoods had poor access to transit and high traffic. Research by the Brookings Institution comparing the value placed on walkability in Washington, DC, showed a strong link between better walkability, on the one hand, and housing prices, retail sales, and housing, office, and retail rents.

Yet, in general, the tools available for home searches make it hard to incorporate transportation and neighborhood composition into the process. Search and filter options typically make it much easier to search by price, size, and number of bedrooms than by proximity to transit, parks, restaurants, and schools, making it hard for homebuyers to easily identify areas of a city that live up to a sustainable and livable neighborhood ideal. They also make it hard to quantify and understand the cost and sustainability tradeoffs of living in one location versus another — for example, when comparing a location close to public transit but far from shops and schools versus a location that has walkable access to shops and schools but only average access to public transit. Those on the hunt for a new home are often left piecing together information from a variety of disparate sources across multiple browser windows and with little help to compare locations apples to apples. None of this is easy, and it often results in shortcuts, leaving homebuyers to rely on their own rough knowledge or the recommendations of others in order to find good sustainable options worth considering.

At Local Logic, we believe this is one of the most important problems to solve to make cities more sustainable in the future. And we know it’s a problem that can be solved.

Today, we are building products to help investors, developers, and homebuyers integrate location intelligence into their decision-making processes. In particular, our products help identify sustainable locations and to understand how to improve the environmental and social impacts of investments over time. At the heart of this effort is our drive to build a digital twin of cities that describes rigorously what is present and absent from different locations compared to a sustainable neighborhood ideal and estimates the transportation and mobility patterns that are likely in each area given what is nearby.

We know that the hulking carbon footprint of personal transportation needs to be tackled on the double. We also know that retailers, employers, and individual homebuyers are interested in living in sustainable neighborhoods, with easy access to nearby transit, shops, schools, and amenities. Our products make it possible to address both challenges.

Get in touch today to learn more about our location insights