Borrower Reality Check

Insights

| 12 Feb 2026

The world’s urban population is expected to grow from its current size of 4.4 billion to 6.7 billion by 2050. Cities are expanding to accommodate this rapid expansion, transforming rural lands into urban areas characterized by low-density single-family dwellings, single-use zoning, and increased car use. This phenomenon is known as urban sprawl.

Urban sprawl seems to go hand in hand with population growth, but it also places residents further away from major centers as people search for increased living space at more affordable prices. Higher energy use, pollution, and traffic congestion have been correlated with this development pattern, as well as a loss in community distinctiveness. We must revisit and adapt residential developments, so they can accommodate the growth of our cities in a sustainable way.

This article explores data on street and population growth — two contributing factors to urban development — in the largest Canadian metro areas to understand urban sprawl and how high-density developments can favor sustainable city growth.

As a way to accommodate an ever-growing population and its need for more residential space, cities expand by building new streets that stretch outside their urban core. Single-family homes quickly fill these areas to meet the demands of people looking for more affordable and spacious housing.

These types of suburban developments create urban landscapes characterized by fewer amenities and points of interest — also known as urban sprawl. Homes, workplaces, and other daily destinations, such as grocery stores, are farther apart in sprawled communities that are low-density. Since public transportation is often underserved in these areas, residents tend to rely on their cars to cover these longer trips.

According to Adam Millard-Ball, an associate professor of environmental studies at UC Santa Cruz, “sprawl is an environmental problem because it makes it difficult for people to walk and to access public transit, which forces them to stay in their cars.” The resulting increase in car usage leaves behind large environmental impacts such as more traffic jams, greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, transportation costs, air pollution, and health risks.

Our team studied street and population growth within different cities in Canada using data from Statistics Canada between 2016 and 2021. Our next step was to visualize the extent of urban sprawl across these metros by overlaying these datasets on city maps.

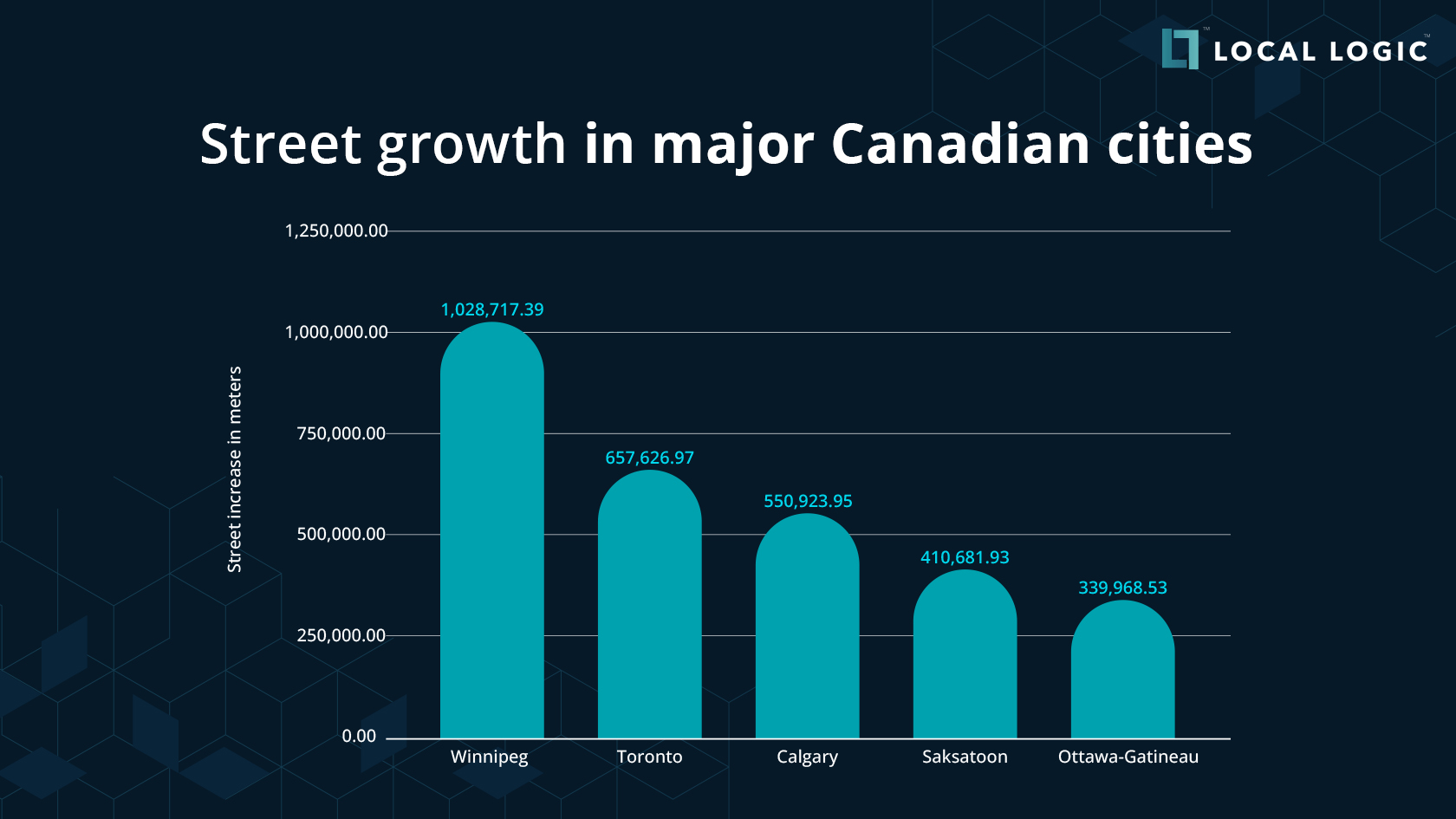

Top five fastest-growing metros by street growth

First, we looked at which metro areas have built the most new streets over the last five years. Here are the cities that made the top of the list:

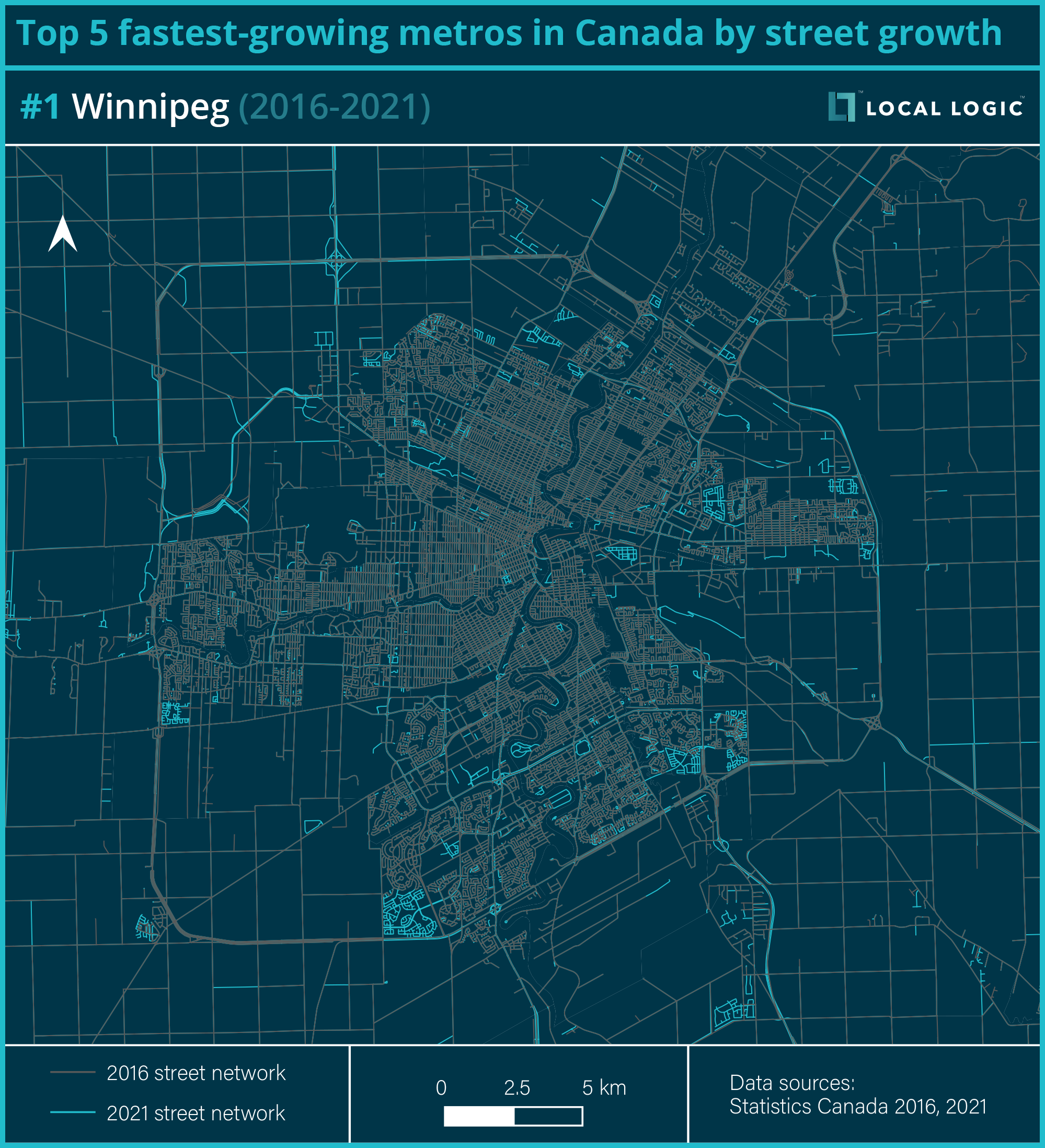

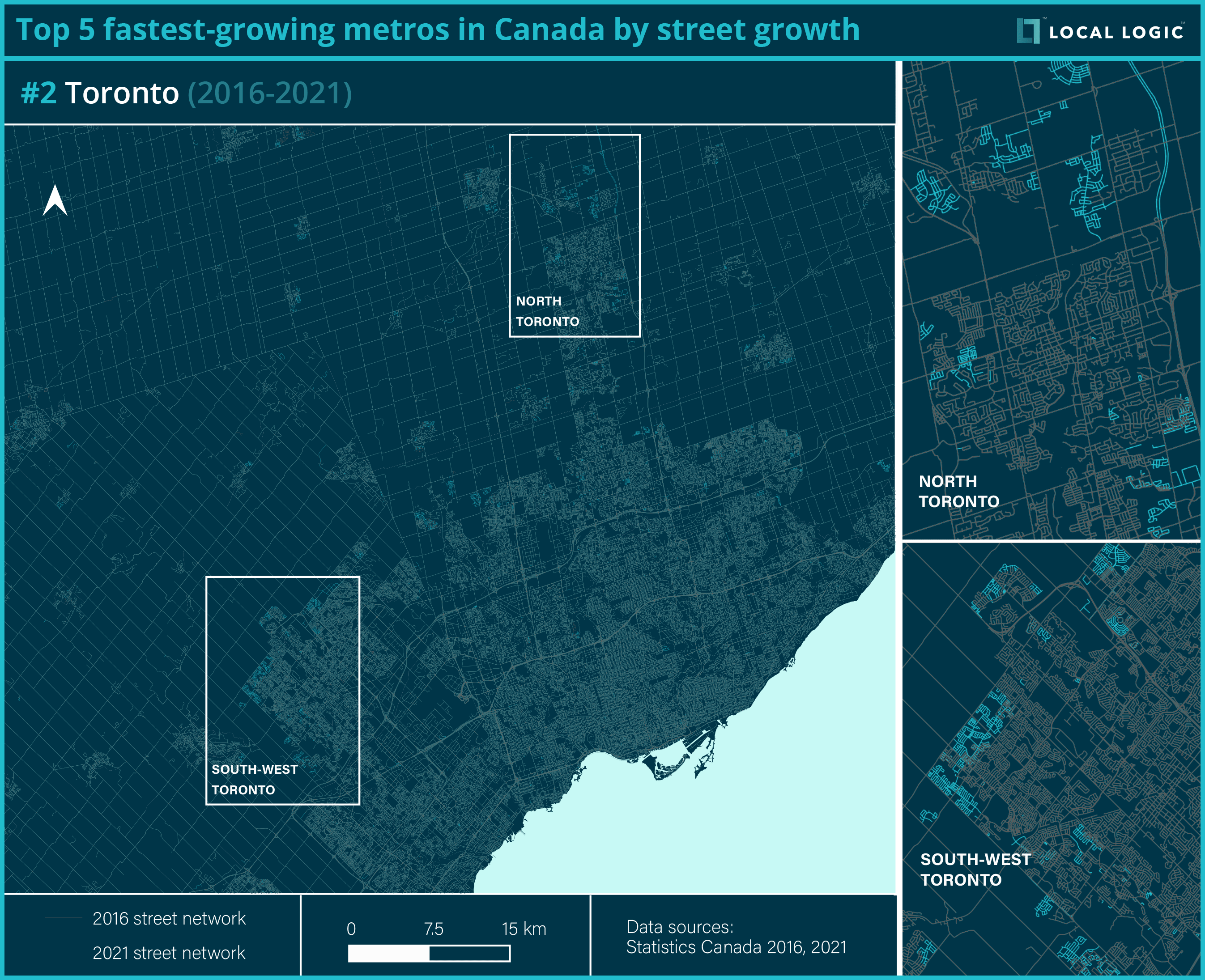

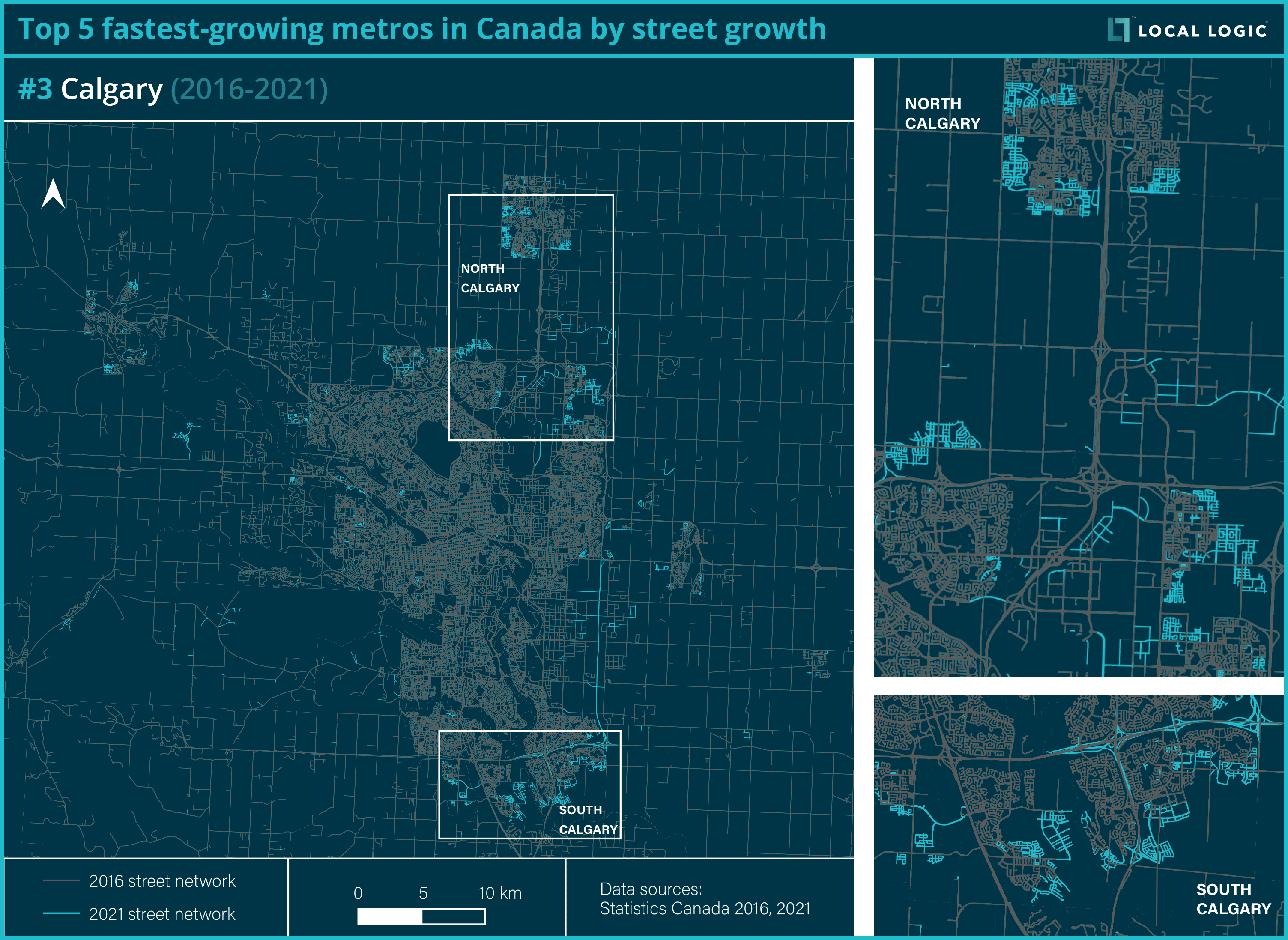

These maps highlight all the new street segments that have been added:

Original map of Trans-Canada Highway via Britannica

In total, 2,988 km have been added to the country’s five largest metropolitan areas between 2016 and 2021. That’s roughly a third of the Trans-Canada Highway, the world’s longest national road that stretches from Victoria, BC to St. John’s, NL for 7,821 km.

The previous maps indicate that new streets are built on the outskirts of the city, away from its center, signaling new developments that are more spread out and decentralized. Reinforcing that notion is a study by Radio-Canada which states, “urban sprawl (up 34%) has progressed on average faster than population growth (up 26%) [with] each Canadian [occupying] more space, farther away from city centers.”

To determine how sprawling a city is, we calculated a sprawl index by dividing the total amount of new streets built by how much the population grew. The higher that number is, the more sprawling the city is as more street segments were built per additional resident.

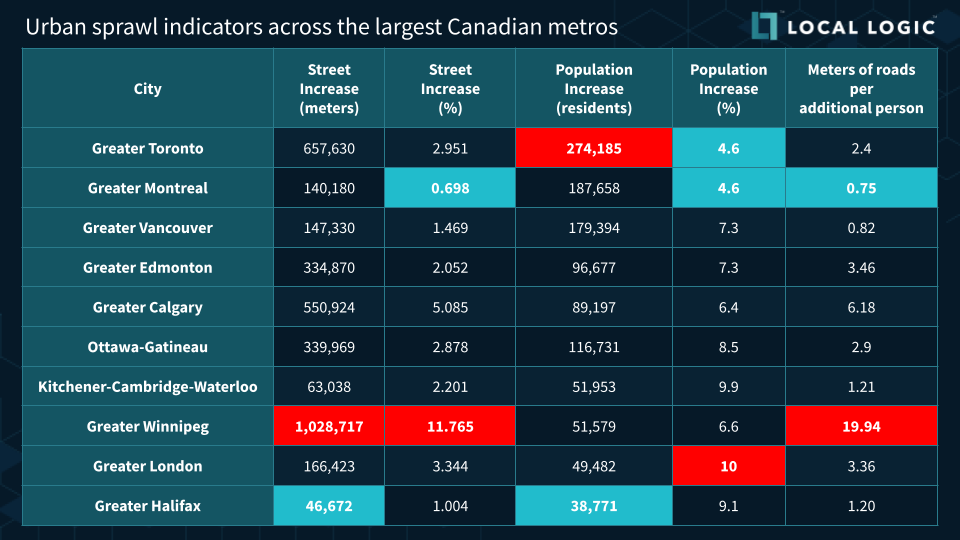

Urban sprawl indicators across the largest Canadian metros

The table above details the relationship between street growth and population growth, and how it impacts the level of sprawl within an urban area. For example, if a city saw a 5% population growth but only a 1% street network growth, it is much less sprawling and more sustainable than another with 1% population growth and 5% street network growth.

Higher density, mixed-use, and walkable neighborhoods are integral components that have been adopted by many cities to combat urban sprawl and its negative impacts.

Sprawl is the result of various socioeconomic forces at play. Since there is a market demand for spacious properties with larger lots, developers are more inclined to build these subdivisions, which in turn creates low-density areas. The municipality also holds decision-making power over the project’s final approval. Thus, shifting away from single-family developments depends on the political will of individual municipalities.

“Without a pretty strong regulatory control, the housing system is going to produce lots of urban sprawl,” says David Wachsmuth, Canada Research Chair in Urban Governance. For instance, if you are only legally allowed to build homes in one part of town and stores in another, then residents have to travel longer distances to get to their destinations.

Regulations and policies take years, sometimes even decades, to be implemented — but thankfully, there is already a noticeable shift towards sustainability in real estate investment, development, and home buying.

Increasing population density along existing street networks can be a sustainable method for accommodating city growth. Instead of building out (with single-family homes), the focus should shift towards building up (with new high-density developments near amenities).

There exists a binary perception that either you have a large urban center with overarching skyscrapers or a quiet suburban low-rise area — with no middle ground. Therefore, some people oppose densification since they believe it is only possible through the construction of high-rise condos. However, this assumption fails to consider that densification can also be achieved through mid- and low-rise apartments, such as triplexes and six-storey complexes.

Even if they would prefer to stay closer to the urban core, the lack of affordable and spacious residences prompts people to move to the suburbs. To slow this exodus to low-density suburbs, Wachsmuth believes that provinces should revise their laws and regulations to permit more housing options, especially for families. Several Canadian cities have already taken steps to close this missing middle gap. In Vancouver and Toronto, in particular, single-family residences can build laneway houses on their property as part of a gentle densification program.

Sprawl is related to a lack of accessibility that prevents people from reaching services and amenities located far away. Often, people have trouble accessing opportunities due to factors like affordability, quality, and diversity of transport options.

A sustainable, less car-dependent urban environment relies heavily on transit access and proximity to services. Densifying existing built-up areas provides greater opportunities and freedom of choice through which people can easily reach their desired destinations, no matter which transportation modes they use.

For example, Chicago implemented a pilot program for Equitable Transit-Oriented Development to encourage the development of high-density, low-parking communities near rapid or high-frequency transit services.

As our global population continues to rise, cities will keep spreading. With seven out of ten people set to live in urban areas by 2050, thoughtful planning will be required to build more sustainable cities. While urban sprawl cannot be halted altogether, its adverse effects can be reduced with data-driven solutions identifying opportunities for sustainable real estate development.

Developers are responsible for making decisions on where to build new housing or office towers. Residents will experience ripple effects from these choices in their daily lives, such as where they live, how they commute, and where they run errands. Most homebuyers also face a similar challenge — they want to live near services and amenities while minimizing their environmental impact.

However, developers and homebuyers both encounter an information gap since they lack concrete data to quantify and understand the value and feel of a location compared to another. There are few tools available for home searches that provide information on modes of transportation and neighborhood characteristics, which makes it difficult to determine where to build or where to live.

Local Logic builds location intelligence solutions that identify sustainable opportunities while highlighting the risk and return associated with them. With our street- and neighborhood-level insights, investors can predict location value with greater accuracy and make more informed decisions on where and what to build.

Location Scores and Points of Interest as seen in Local Logic’s Local Content

Additionally, we developed 18 proprietary Location Scores that measure proximity to amenities and mobility patterns. Using our location insights, investors can create their own investment thesis to find properties based on specific criteria, such as high-density areas and access to services when building with sustainability in mind.

Curious to know how location insights can help you?

Get in touch with our team to learn more.